February 15, 2026, By Dean Hoke – Through my ongoing work with Small College America and Edu Alliance Group, I’ve researched dozens of rural and small-town campuses and interviewed presidents, faculty, and community leaders across the country. I keep encountering a pattern that rarely makes the national conversation about higher education’s future.

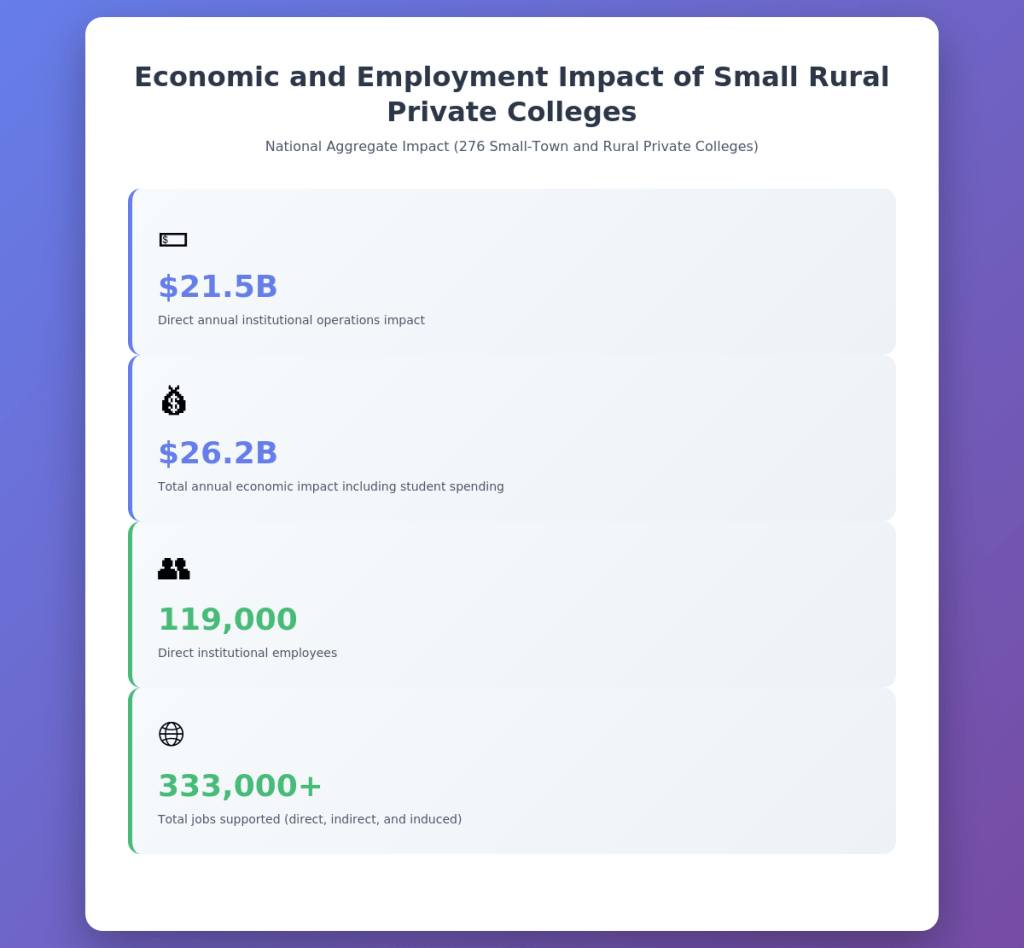

The economic case for small rural colleges is straightforward and substantial. Across 276 small-town and rural private colleges in America, institutional operations generate an estimated $21.5 billion in annual economic impact. Add student spending, and the total reaches roughly $26.2 billion. These institutions directly employ nearly 119,000 people, with total employment impact exceeding 333,000 jobs when accounting for indirect and induced effects. These institutions serve the 66.3 million Americans—roughly 20 percent of the U.S. population—who live in Census-defined rural areas.

Those numbers matter. But the multiplier, as compelling as it is, tells only part of the story.

In communities where local journalism has collapsed, where city governments lack planners or grant writers, and where technical expertise is scarce, small colleges increasingly function as something more fundamental than economic anchors.

They serve as a distributed knowledge infrastructure.

In many rural regions, they are the only institutions capable of conducting research, convening stakeholders, analyzing complex problems, and producing evidence-based recommendations. When difficult questions arise, who can evaluate this policy? Who has access to data? Who can design a solution? Rural communities often turn to their local college. Not because it is the best option among many. But because it is the only option.

“When Hendrix thrives, Conway thrives, and when Conway thrives, Hendrix thrives,” Dr. Karen K. Petersen, President of Hendrix College in Conway, Arkansas, told me. “There’s just no way for one of us separately to thrive and the other not.” Beyond shared prosperity, she sees an ecosystem at risk. If these colleges hollow out across the middle of the country, she warns, it is not simply a loss for higher education; it is a loss for the republic.

The question facing rural and small-town America is not just what happens when a college closes. It is who fills the knowledge vacuum left behind.

The Capacity Gap in Rural Communities

At the Education Writers Association’s 2025 Higher Education Seminar on rural education, panelists emphasized a critical distinction that deserves broader attention. Rural communities do not lack ambition; they lack capacity.

Many counties simply do not employ research analysts, planners, or grant writers capable of navigating federal infrastructure funding or complex policy design. Colleges frequently step into that space—convening stakeholders, hosting workshops, applying for grants, coordinating broadband expansion, and facilitating healthcare initiatives.

This capacity gap extends beyond federal funding. According to a 2024 Trust for Civic Life survey of over 500 rural residents, rural Americans trust local institutions, such as schools, churches, and community businesses, far more than national organizations. When complex problems arise, rural communities turn to the institutions they know. Increasingly, that means turning to their local colleges, even if those institutions weren’t originally designed for such roles.

In many counties, the college is the only entity with:

- Research infrastructure

- Analytical capacity

- Convening power

- Multi-disciplinary expertise

Remove the college and you do not simply lose tuition revenue or student housing demand. You lose the region’s primary source of knowledge production.

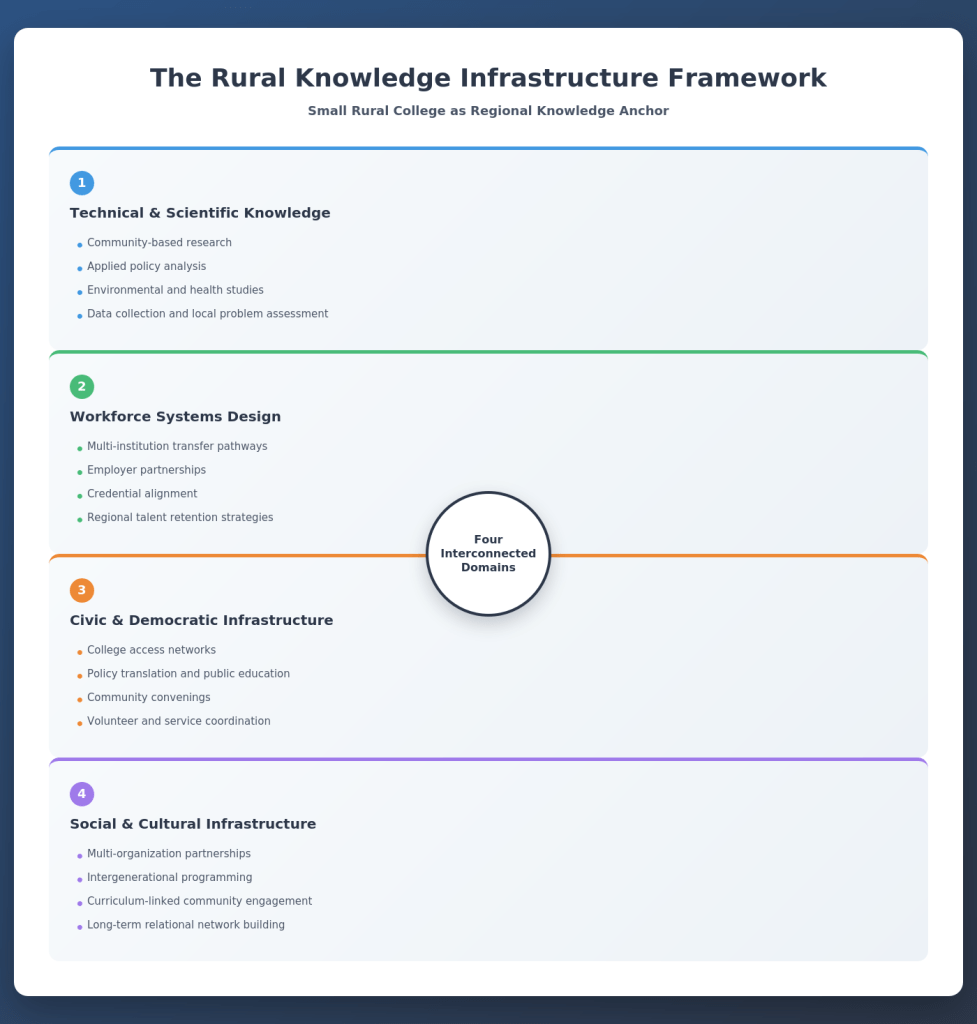

Four Domains of Knowledge Work

What does this knowledge infrastructure look like in practice? Across the country, small rural colleges operate in four distinct but overlapping domains.

1. Technical and Scientific Knowledge

In 2023, students at Hendrix College conducted a telephone survey of 901 older Arkansans as part of an Advanced Policy Analysis course. The project, developed in partnership with the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences and AARP Arkansas, aimed to evaluate how communities could better serve aging populations.

The findings were striking: Conway—despite relative prosperity—ranked lowest among surveyed communities as a place to retire. Students analyzed transportation barriers, housing access, and social isolation, then presented policy recommendations at a public symposium attended by civic leaders and national AARP representatives.

Here is the question worth asking: Who would have conducted that survey if Hendrix did not exist?

Conway, a city of 59,000, does not employ research analysts. Contracting a private consulting firm would cost tens of thousands of dollars. The study likely would not have happened.

Across the country, similar patterns emerge. Environmental science students test regional water quality. Computer science students build nonprofit websites. Engineering students troubleshoot manufacturing systems. These projects may not always produce journal publications. But they produce something equally valuable to rural communities: locally actionable knowledge that would otherwise go uncreated.

2. Workforce Development Knowledge

When Arkansas officials documented a shortage of approximately 9,000 nurses, Lyon College in Batesville did more than launch a nursing major. It orchestrated a regional pipeline.

Lyon developed formal partnerships with White River Health, Arkansas State University-Newport, Ozarka College, and the University of Arkansas Community College at Batesville. Students begin liberal arts coursework at Lyon, transfer for RN licensure, then return to complete a BSN. Working nurses can finish degrees online at deliberately affordable tuition rates, with significant transfer credits applied.

This was not simply program development. It was system design.

The college identified a regional workforce shortage, convened institutions that historically operated independently, negotiated articulation agreements, aligned curricula, and built an infrastructure that retains healthcare workers locally.

In many rural communities, no other institution has the legitimacy, convening authority, and organizational stability to accomplish this kind of coordination. The college becomes a knowledge broker—connecting employers, students, technical programs, and policymakers.

3. Civic and Democratic Knowledge

In rural Kentucky, Berea College operates Partners for Education, serving the Appalachian counties through a network of full-time specialists providing academic intervention, college counseling, and wraparound services.

The program places staff directly in rural schools, offers Advanced Placement preparation, assists with college applications, and runs volunteer income tax preparation programs serving low-income families. It employs over 100 AmeriCorps volunteers annually and coordinates services across multiple counties.

This is not incidental service. It is institutionalized civic infrastructure.

When a student in Clay County aspires to attend college, Berea’s specialists navigate financial aid, admissions testing, and bureaucratic systems that under-resourced schools cannot manage alone. When families need help accessing earned income tax credits, Berea-trained volunteers assist. Remove the college, and the network dissolves.

The knowledge infrastructure here is not abstract research—it is the expertise required to translate policy into opportunity.

4. Social and Cultural Knowledge

In Swannanoa, North Carolina, Warren Wilson College coordinates the Verner Experiential Gardens—a multi-organization partnership with early childhood educators and nonprofit partners.

College students work alongside young children, developing food systems education, outdoor curriculum, and intergenerational learning environments. The partnership requires sustained coordination, curriculum integration, infrastructure management, and evaluation.

Individual volunteers can serve a meal, and Institutions build systems.

This quieter work—relationship-building, curriculum alignment, multi-year coordination—rarely appears in rankings or federal datasets. But it shapes long-term community resilience.

The Counterfactual: What Happens When Colleges Close?

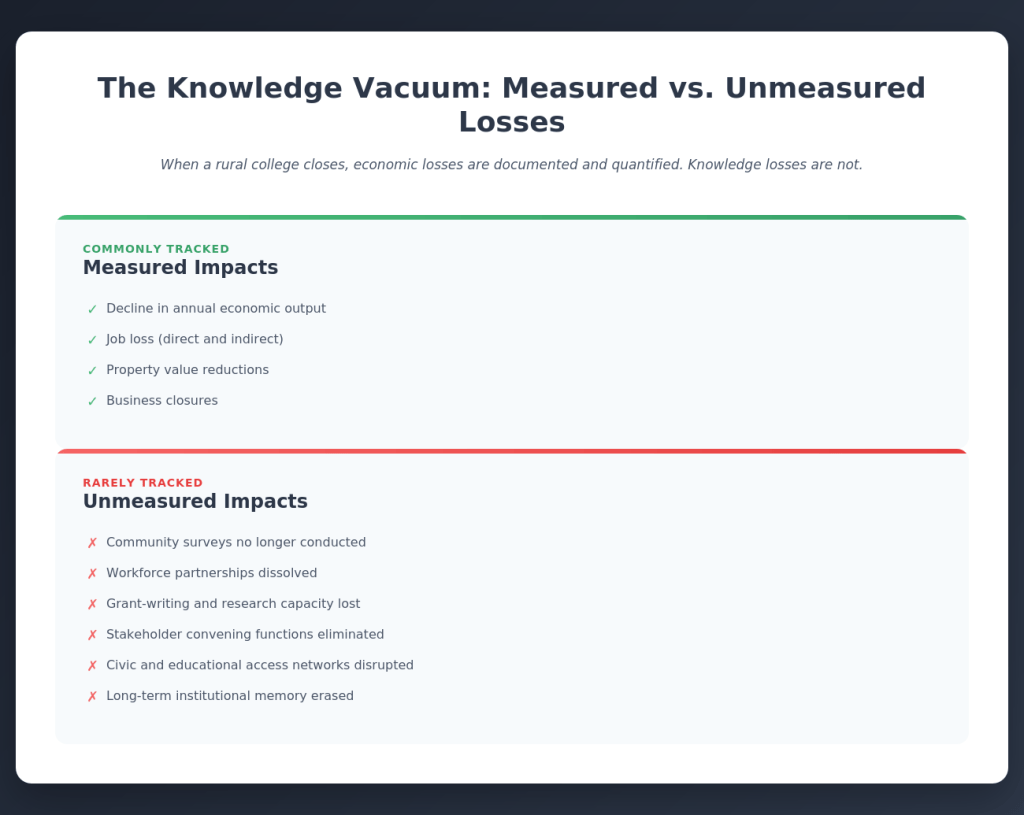

Economic impact studies estimate that a small college closure can eliminate roughly $32 million in annual output and hundreds of jobs. Property values decline. Businesses shutter. Young professionals leave.

But the knowledge loss is harder to quantify—and more damaging over time.

Who conducts the next community survey? Who negotiates the next workforce pipeline? Who coordinates regional college access initiatives? Who convenes hospitals, schools, and nonprofits around emerging challenges?

In major metropolitan areas, other universities, think tanks, and consulting firms can step in. In rural regions, there often is no alternative provider. When a college closes, the community loses:

- Research capacity

- Stakeholder convening power

- Multi-disciplinary expertise

- Alumni networks and institutional memory

- Grant relationships with state and federal agencies

Infrastructure like this takes decades to build. It can vanish in months.

The Measurement Problem

Part of the challenge lies in how we measure higher education value.

Federal data systems such as IPEDS focus heavily on first-time, full-time, degree-seeking students. Adult learners, part-time enrollees, noncredit workforce trainees, and transfer preparation work are often undercounted or invisible.

The four domains described above—community surveys, workforce pipelines, civic partnerships, regional coordination—generate almost no federal metrics. We reward enrollment and graduation numbers. We ignore regional knowledge production.

The result is a mismatch between what rural colleges do for their communities and what public policy measures. When you measure the wrong outputs, you misjudge what is worth preserving.

Policy Implications: Recognizing Knowledge Infrastructure

If small rural colleges function as distributed knowledge infrastructure, policy must reflect that reality.

First, states should create Rural Knowledge Partnership Grants—competitive funding streams that reward documented college-community problem-solving initiatives.

Second, federal agencies should expand community-engaged research funding targeted specifically at small and mid-sized institutions serving rural regions.

Third, state economic development strategies should formally integrate colleges as implementation partners in broadband, healthcare, workforce, and infrastructure initiatives.

Fourth, foundations concerned about rural resilience should treat colleges not merely as grantees, but as anchor intermediaries capable of coordinating multi-sector coalitions.

These changes do not require new institutions. They require recognizing what already exists.

What We Stand to Lose

President Petersen describes Hendrix as ‘scrappy,’ an institution that ‘punches above its weight.’ But she worries about the broader ecosystem of small colleges across the middle of the country.

The demographic headwinds are real. The financial pressures are mounting. Elite institutions attract disproportionate philanthropic attention. Meanwhile, rural-serving colleges operate in relative obscurity. Yet as rural America faces aging populations, workforce shortages, infrastructure deficits, and civic fragmentation, the institutions most capable of addressing these challenges are themselves under strain.

We often talk about colleges as if they are simply educational providers. In rural America, they are something more. They are the institutional capacity to ask complex questions. They are the convening power that aligns fragmented stakeholders. They are the research engines capable of producing evidence-based solutions.

When a rural college closes, we count the lost jobs and shuttered dormitories. We rarely measure the knowledge vacuum. We do not count the surveys never conducted, the partnerships never negotiated, the civic programs dissolved, the problem-solving capacity eroded.

Infrastructure is not only roads, water systems, and broadband. It is the ability to solve problems. In many rural counties, that capacity resides primarily inside one institution: the local college. The question is not whether America can afford to sustain these institutions. The question is whether rural communities can function without them.

If we are honest about existing capacity gaps—if we recognize that knowledge infrastructure takes decades to build and weeks to dismantle—the answer becomes clear. Small rural colleges are not luxuries we can no longer afford. They are necessities we cannot afford to lose. Not because they are historic or charming. But because they perform work that no one else is doing, in places that desperately need it done.

Dean Hoke is Managing Partner of Edu Alliance Group, a higher education consultancy, and a Senior Fellow for The Sagamore Institute. He formerly served as President/CEO of the American Association of University Administrators (AAUA).

Dean has worked with higher education institutions worldwide. With decades of experience in higher education leadership, consulting, and institutional strategy, he brings a wealth of knowledge on small colleges’ challenges and opportunities. Dean is the Executive Producer and co-host for the podcast series Small College America.