The Growing Movement to Reform Research Assessment and Rankings

By Dean Hoke, September 22, 2025: For the past fifteen years, I have been closely observing what can only be described as a worldwide fascination—if not obsession—with university rankings, whether produced by Times Higher Education, QS, or U.S. News & World Report. In countless conversations with university officials, a recurring theme emerges: while most acknowledge that rankings are often overused by students, parents, and even funders when making critical decisions, few deny their influence. Nearly everyone agrees that rankings are a “necessary evil”—flawed, yet unavoidable—and many institutions still direct significant marketing resources toward leveraging rankings as part of their recruitment strategies.

It is against this backdrop of reliance and ambivalence that recent developments, such as Sorbonne University’s decision to withdraw from THE rankings, deserve closer attention

In a move that signals a potential paradigm shift in how universities position themselves globally, Sorbonne University recently announced it will withdraw from the Times Higher Education (THE) World University Rankings starting in 2026. This decision isn’t an isolated act of defiance—Utrecht University had already left THE in 2023, and the Coalition for Advancing Research Assessment (CoARA), founded in 2022, has grown to 767 members by September 2025. Together, these milestones reflect a growing international movement that questions the very foundations of how we evaluate academic excellence.

The Sorbonne Statement: Quality Over Competition

Sorbonne’s withdrawal from THE rankings isn’t merely about rejecting a single ranking system. It appears to be a philosophical statement about what universities should stand for in the 21st century. The institution has made it clear that it refuses to be defined by its position in what it sees as commercial ranking matrices that reduce complex academic institutions to simple numerical scores.

Understanding CoARA: The Quiet Revolution

The Coalition for Advancing Research Assessment represents one of the most significant challenges to traditional academic evaluation methods in decades. Established in 2022, CoARA has grown rapidly to include 767 member organizations as of September 2025. This isn’t just a European phenomenon—though European institutions have been early and enthusiastic adopters. The geographic distribution of CoARA members tells a compelling story about where resistance to traditional ranking systems is concentrated. As the chart shows, European countries dominate participation, led by Spain and Italy, with strong engagement also from Poland, France, and several Nordic countries. This European dominance isn’t accidental—the region’s research ecosystem has long been concerned about the Anglo-American dominance of global university rankings and the way these systems can distort institutional priorities.

The Four Pillars of Reform

CoARA’s approach centers on four key commitments that directly challenge the status quo:

1. Abandoning Inappropriate Metrics The agreement explicitly calls for abandoning “inappropriate uses of journal- and publication-based metrics, in particular inappropriate uses of Journal Impact Factor (JIF) and h-index.” This represents a direct assault on the quantitative measures that have dominated academic assessment for decades.

2. Avoiding Institutional Rankings Perhaps most relevant to the Sorbonne’s decision, CoARA commits signatories to “avoid the use of rankings of research organisations in research assessment.” This doesn’t explicitly require withdrawal from ranking systems, but it does commit institutions to not using these rankings in their own evaluation processes.

3. Emphasizing Qualitative Assessment The coalition promotes qualitative assessment methods, including peer review and expert judgment, over purely quantitative metrics. This represents a return to more traditional forms of academic evaluation, albeit updated for modern needs.

4. Responsible Use of Indicators Rather than eliminating all quantitative measures, CoARA advocates for the responsible use of indicators that truly reflect research quality and impact, rather than simply output volume or citation counts.

European Leadership

Top 10 Countries by CoARA Membership:

The geographic distribution of CoARA members tells a compelling story about where resistance to traditional ranking systems is concentrated. As the chart shows, European countries dominate participation, led by Spain and Italy, with strong engagement also from Poland, France, and several Nordic countries. This European dominance isn’t accidental—the region’s research ecosystem has long been concerned about the Anglo-American dominance of global university rankings and the way these systems can distort institutional priorities.

The geographic distribution of CoARA members tells a compelling story about where

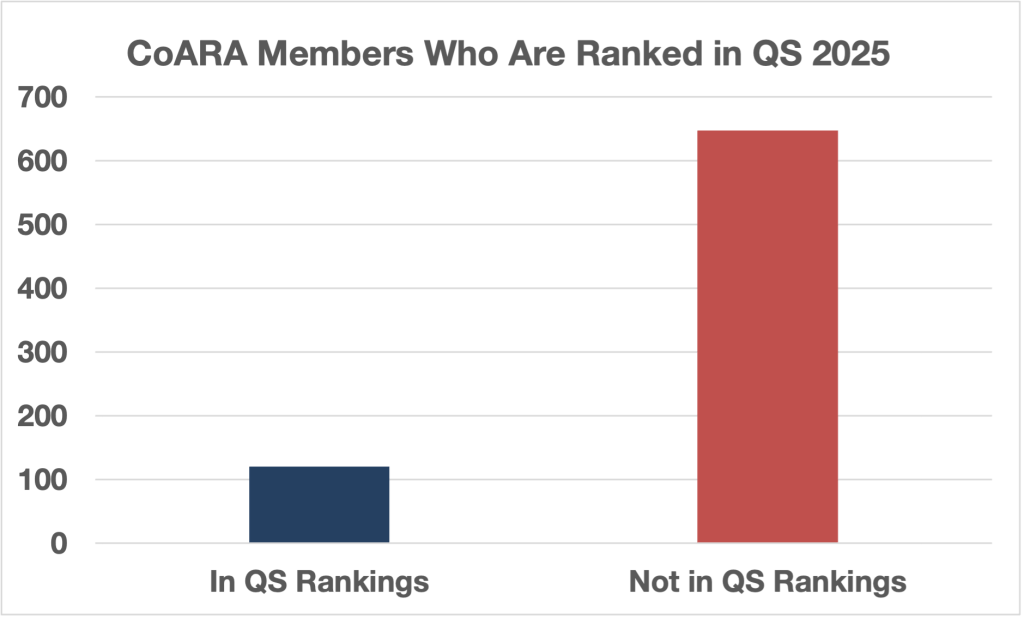

Prestigious European universities like ETH Zurich, the University of Zurich, Politecnico di Milano, and the University of Manchester are among the members, lending credibility to the movement. However, the data reveals that the majority of CoARA members (84.4%) are not ranked in major global systems like QS, which adds weight to critics’ arguments about institutional motivations.

CoARA Members Ranked vs Not Ranked in QS:

The Regional Divide: Participation Patterns Across the Globe

What’s particularly striking about the CoARA movement is the relative absence of U.S. institutions. While European universities have flocked to join the coalition, American participation remains limited. This disparity reflects fundamental differences in how higher education systems operate across regions.

American Participation: The clearest data we have on institutional cooperation with ranking systems comes from the United States. Despite some opposition to rankings, 78.1% of the nearly 1,500 ranked institutions returned their statistical information to U.S. News in 2024, showing that the vast majority of American institutions remain committed to these systems. However, there have been some notable American defections. Columbia University is among the latest institutions to withdraw from U.S. News & World Report college rankings, joining a small but growing list of American institutions questioning these systems. Yet these remain exceptions rather than the rule.

European Engagement: While we don’t have equivalent participation rate statistics for European institutions, we can observe their engagement patterns differently. 688 universities appear in the QS Europe ranking for 2024, and 162 institutions from Northern Europe alone appear in the QS World University Rankings: Europe 2025. However, European institutions have simultaneously embraced the CoARA movement in large numbers, suggesting a more complex relationship with ranking systems—continued participation alongside philosophical opposition.

Global Participation Challenges: For other regions, comprehensive participation data is harder to come by. The Arab region has 115 entries across five broad areas of study in QS rankings, but these numbers reflect institutional inclusion rather than active cooperation rates. It’s important to note that some ranking systems use publicly available data regardless of whether institutions actively participate or cooperate with the ranking organizations.

This data limitation itself is significant—the fact that we have detailed participation statistics for American institutions but not for other regions may reflect the more formalized and transparent nature of ranking participation in the U.S. system versus other global regions.

American universities, particularly those in the top tiers, have largely benefited from existing ranking systems. The global prestige and financial advantages that come with high rankings create powerful incentives to maintain the status quo. For many American institutions, rankings aren’t just about prestige—they’re about attracting international students, faculty, and research partnerships that are crucial to their business models.

Beyond Sorbonne: Other Institutional Departures

Sorbonne isn’t alone in taking action. Utrecht University withdrew from THE rankings earlier, citing concerns about the emphasis on scoring and competition. These moves suggest that some institutions are willing to sacrifice prestige benefits to align with their values. Interestingly, the Sorbonne has embraced alternative ranking systems such as the Leiden Open Rankings, which highlight its impact.

The Skeptics’ View: Sour Grapes or Principled Stand?

Not everyone sees moves like Sorbonne’s withdrawal as a noble principle. Critics argue that institutions often raise philosophical objections only after slipping in the rankings. As one university administrator put it: “If the Sorbonne were doing well in the rankings, they wouldn’t want to leave. We all know why self-assessment is preferred. ‘Stop the world, we want to get off’ is petulance, not policy.”

This critique resonates because many CoARA members are not major players in global rankings, which fuels suspicion that reform may be as much about strategic positioning as about values. For skeptics, the call for qualitative peer review and expert judgment risks becoming little more than institutions grading themselves or turning to sympathetic peers.

The Stakes: Prestige vs. Principle

At the heart of this debate is a fundamental tension: Should universities prioritize visibility and prestige in global markets, or focus on measures of excellence that reflect their mission and impact? For institutions like the Sorbonne, stepping away from THE rankings is a bet that long-term reputation will rest more on substance than on league table positions. But in a globalized higher education market, the risk is real—rankings remain influential signals to students, faculty, and research partners.

Rankings also exert practical influence in ways that reformers cannot ignore. Governments frequently use global league tables as benchmarks for research funding allocations or as part of national excellence initiatives. International students, particularly those traveling across continents, often rely on rankings to identify credible destinations, and faculty recruitment decisions are shaped by institutional prestige. In short, rankings remain a form of currency in the global higher education market.

This is why the decision to step away from them carries risk. Institutions like the Sorbonne and Utrecht may gain credibility among reform-minded peers, but they could also face disadvantages in attracting international talent or demonstrating competitiveness to funders. Whether the gamble pays off will depend on whether alternative measures like CoARA or ROI rankings achieve sufficient recognition to guide these critical decisions.

The Future of Academic Assessment

The CoARA movement and actions like Sorbonne’s withdrawal represent more than dissatisfaction with current ranking systems—they highlight deeper questions about what higher education values in the 21st century. If the movement gains further momentum, it could push institutions and regulators to diversify evaluation methods, emphasize collaboration over competition, and give greater weight to societal impact.

Yet rankings are unlikely to disappear. For students, employers, and funders, they remain a convenient—if imperfect—way to compare institutions across borders. The practical reality is that rankings will continue to coexist with newer approaches, even as reform efforts reshape how universities evaluate themselves internally.

Alternative Rankings: The Rise of Outcome-Based Assessment

While CoARA challenges traditional rankings, a parallel trend focuses on outcome-based measures such as return on investment (ROI) and career impact. Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce, for example, ranks more than 4,000 colleges on the long-term earnings of their graduates. Its findings tell a very different story than research-heavy rankings—Harvey Mudd College, which rarely appears at the top of global research lists, leads ROI tables with graduates projected to earn $4.5 million over 40 years.

Other outcome-oriented systems, such as The Princeton Review’s “Best Value” rankings, emphasize affordability, employment, and post-graduation success. These approaches highlight institutions that may be overlooked by global research rankings but deliver strong results for students. Together, they represent a pragmatic counterbalance to CoARA’s reform agenda, showing that students and employers increasingly want measures of institutional value beyond research metrics alone.

These alternative models can be seen most vividly in rankings that emphasize affordability and career outcomes. *The Princeton Review’s* “Best Value” rankings, for example, combine measures of financial aid, academic rigor, and post-graduation outcomes to highlight institutions that deliver strong returns for students relative to their costs. Public universities often rise in these rankings, as do specialized colleges that may not feature prominently in global research tables.

Institutions like the Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences illustrate this point. Although virtually invisible in global rankings, Albany graduates report median salaries of $124,700 just ten years after graduation, placing the college among the best in the nation on ROI measures. For students and families making education decisions, data like this often carries more weight than a university’s position in QS or THE.

Together with Georgetown’s ROI rankings and the example of Harvey Mudd College, these cases suggest that outcome-based rankings are not marginal alternatives—they are becoming essential tools for understanding institutional value in ways that matter directly to students and employers.

Rankings as Necessary Evil: The Practical Reality

The CoARA movement and actions like Sorbonne’s withdrawal represent more than just dissatisfaction with current ranking systems. They reflect deeper questions about the values and purposes of higher education in the 21st century.

If the movement gains momentum, we could see:

Diversification of evaluation methods, with different regions and institution types developing assessment approaches that align with their specific values and goals

Reduced emphasis on competition between institutions in favor of collaboration and shared improvement

Greater focus on societal impact rather than purely academic metrics

More transparent and open assessment processes that allow for a better understanding of institutional strengths and contributions

Conclusion: Evolution, Not Revolution

The Coalition for Advancing Research Assessment and decisions like Sorbonne’s withdrawal from THE rankings represent important challenges to how we evaluate universities, but they signal evolution rather than revolution. Instead of the end of rankings, we are witnessing their diversification. ROI-based rankings, outcome-focused measures, and reform initiatives like CoARA now coexist alongside traditional global league tables, each serving different audiences.

Skeptics may dismiss reform as “sour grapes,” yet the concerns CoARA raises about distorted incentives and narrow metrics are legitimate. At the same time, American resistance reflects both philosophical differences and the pragmatic advantages U.S. institutions enjoy under current systems.

The most likely future is a pluralistic landscape: research universities adopting CoARA principles internally while maintaining a presence in global rankings for visibility; career-focused institutions highlighting ROI and student outcomes; and students, faculty, and employers learning to navigate multiple sources of information rather than relying on a single hierarchy.

In an era when universities must demonstrate their value to society, conversations about how we measure excellence are timely and necessary. Whether change comes gradually or accelerates, the one-size-fits-all approach is fading. A more complex mix of measures is emerging—and that may ultimately serve students, institutions, and society better than the systems we are leaving behind. In the end, what many once described to me as a “necessary evil” may persist—but in a more balanced landscape where rankings are just one measure among many, rather than the single obsession that has dominated higher education for so long.

Dean Hoke is Managing Partner of Edu Alliance Group, a higher education consultancy. He formerly served as President/CEO of the American Association of University Administrators (AAUA). Dean has worked with higher education institutions worldwide. With decades of experience in higher education leadership, consulting, and institutional strategy, he brings a wealth of knowledge on colleges’ challenges and opportunities. Dean is the Executive Producer and co-host for the podcast series Small College America.

By

By