By Dr. Jay Noren. During the past two decades, state and federal funding trends have significantly reduced student access to higher education programs. State funding has decreased continually for the past two decades and most recent federal tax reform and financial aid administrative actions have further diminished overall higher education funding and access. Four areas are of most significance:

By Dr. Jay Noren. During the past two decades, state and federal funding trends have significantly reduced student access to higher education programs. State funding has decreased continually for the past two decades and most recent federal tax reform and financial aid administrative actions have further diminished overall higher education funding and access. Four areas are of most significance:

- State direct appropriations for higher education funding

- Federal tax changes affecting charitable contributions to college and university foundations

- Increased taxes on college and university endowments

- Student financial aid

The impact of these state and federal actions are separate from the impact that will result from the legislative reauthorization of the Higher Education Act which could occur in the current Congressional session but will more likely occur in the next Congress following the 2018 elections.

State Budget and Policy Issues

State Direct Appropriations for Higher Education

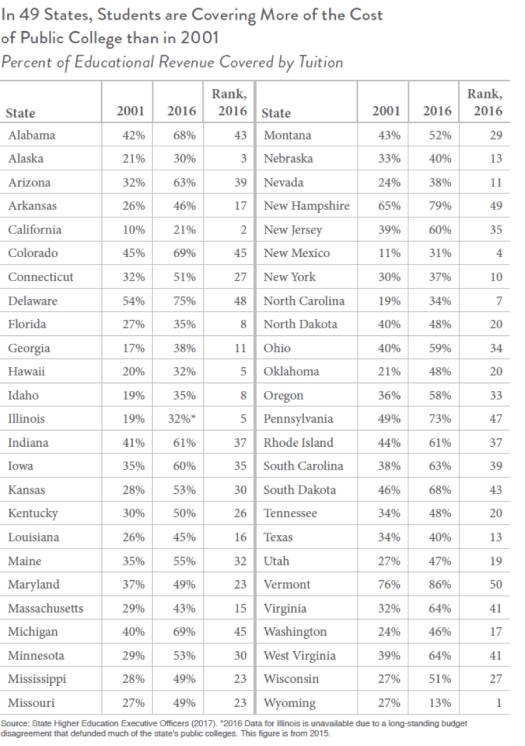

Since 2001, in 49 out of 50 states, higher education appropriations have decreased and tuition revenues have increased substantially as share of funding for public colleges and universities. In 2016 tuition revenues accounted for more than 50% of public college and university budgets in 22 states. Fifteen years earlier, in 2001, only two states depended upon tuition revenues for more than 50% of public college and university budgets. Between 2001 and 2016, 36 states increased the percentage share of dependence on tuition by more than 50%1. The state by state trends are as follows:

More recent state higher education funding trends continue to pose challenges. A January 2018 report by the Association of State Colleges and Universities stated: “Beyond uncertainty emanating from Washington, lawmakers in many states will have challenging sessions due to stagnant state revenue growth. A strong national economy has not led to concomitant revenue growth in many states… these dynamics foreshadow ambiguity and difficult budgetary choices that could lay ahead for lawmakers in many states in 2018 legislative sessions.”8 Additionally, since federal funds transfers to states amount to an average nationally of 33% of state revenues, recent Congressional consideration of future reductions in federal funding of large state-based programs such as Medicaid could very substantially reduce state funding for higher education. Current Congressional leadership members have strongly advocated recently for such federal funding reductions. The National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO) December 2017 report noted that state budget expenditures grew only 2.3 percent in fiscal year 2017 compared to the previous year which is the lowest increase since the 2008 recession and was a key factor leading to Moody’s Investor Service downgrading higher education’s financial outlook from stable to negative in December 2017.8

Federal Higher Education Specific Budget and Policy Issues

At the Federal level, the two most directly relevant actions are: 1-provisions specific to higher education in the tax reform legislation enacted in December 2017 and 2-US Department of Education administrative considerations on financial aid, particularly related to federal student loan programs.

Federal Tax on Charitable Contributions to Higher Education

The projected impact of the federal tax reform bill on charitable contributions to higher education are far-reaching. The most significant tax revision is doubling the standard deduction that taxpayers can claim. Indiana University’s Lilly Family School of Philanthropy estimates that 80 percent fewer taxpayers would itemize for charitable giving under the new law which will directly reduce the level of charitable donations overall2. The impact of reduced charitable donations to public colleges and universities most significantly affects student financial aid. When considered in the context of decreased state appropriation the result is even greater pressure on increased tuition, adding to the already powerful tuition increase pressure of the past two decades. The critical result is decreased access to higher education opportunity. In addition to financial aid the changes also markedly reduce private gift support for the college/university research enterprise.

The doubled standard deduction in the new tax reform law clearly affects charitable giving well beyond higher education as well. A report by the Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation estimates the 2017 tax reform legislation will result in a $95-billion drop in total charitable giving nationwide amounting to a 40% reduction overall. The reduction in higher education contributions has been estimated at $13 billion reduction.4

Federal Tax on College and University Endowments

The final tax reform legislation in December 2017 created a new tax on college and university endowments that creates an unprecedented approach departing from the long-established tax policy that exempts non-profit higher education institutions from taxation on these funds. Although the final tax legislation limits the tax to very large endowments defined as institutions with levels greater than $500,000 per student enrollment, it nonetheless raises great concern that the precedent could expand in the future to taxing endowments in a much larger proportion of colleges and universities3. The precedent has raised very serious concerns in the higher education philanthropic enterprise. Reliance on endowments for scholarships, capital improvements, and research is a critical element of the financial health of higher education. Endowment funding is key to productive research across all disciplines and student support at both the undergraduate and graduate level.

The debate on this issue continues. In early March a new bill, “The Don’t Tax Higher Education Act,” was co-sponsored by Rep. John Delaney, Democrat of Maryland, and Rep. Bradley Byrne, Republican of Alabama. This bill would reverse the tax on endowments and Congressman Byrne commented on his bill: “We should all be looking for ways to increase access to higher education, and endowments play a very important role in funding scholarships, student aid, and important research initiatives.”

Student Financial Aid

In addition to the impact on student financial aid resources from higher education charitable contributions and endowments, other federal proposed tax and administrative actions have further potential major impact. The tax bill proposed in 2017 in the House of Representatives included a provision to tax as income tuition waivers provided to graduate students. Additionally the House bill would have eliminated the deductions for several forms of financial aid including deductions for up to $2,500 of interest paid on student loans; the Hope Scholarship Tax Credit, worth up to $2,500; the Lifetime Learning Credit up to $2,000; and the $5,250 corporate deduction for employee education-assistance plans.5 Fortunately for students, these provisions were eliminated in the Senate bill and the final legislation. However, concerns in the higher education community continues given the level of support that existed in Congress during deliberations on these provisions and the potential that such provisions might be revisited in future tax legislation.

Federal student loan provisions have also been recently reviewed by the Department of Education’s Office of Inspector General, which issued its report January 31, 2018. The report noted that the Federal Student Aid Office Strategic Plan for fiscal years 2015–2019 stated that as more students select income-driven repayment (IDR) plans that allow for student loan forgiveness, the cost could be a major issue for the Federal government. These aid programs benefitted 5 million student in FY2016, an increase from 700,000 in FY 2011, and the Department of Education set a goal of 7 million student IDR loans for FY 2017.

The Inspector General’s January 2018 review covered cost information for the income-driven repayment (IDR) plans, including Pay as You Earn (PAYE), the Revised Pay as You Earn (REPAYE), the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program, and Teacher Loan Forgiveness (TLF) program. The analysis raised concerns that the amount of federal student loans provided is in excess of the trends in repayment and the difference is increasing substantially. The Inspector General’s report noted that the problem is due to the increased income-driven repayment (IDR) loans, which allow students to repay their loans over an extended time period in correlation to their actual income. These plans have increased 625 percent between 2011 fiscal year and 2015 fiscal year. The income-driven repayment loan amount has increased from $7.1 billion in FY 2011 to $51.5 billion in FY 2015 resulting in a federal subsidy cost increase of 748 percent (from $1.4 billion to $11.5 billion).6

The Office of Inspector General has directed the Department of Education to develop a corrective plan for the problem within 30 days (a March 2018 deadline). It also is possible the problem could be addressed in the reauthorization of the Higher Education Act, but it is unlikely that reauthorization will occur as early as March 2018. If there is no corrective action within six months, the matter is then referred to Congress.

The response to this report has the potential for major impact on several million students who depend upon these loans for their access to higher education opportunities.

Trends in Higher Education Attainment in the United States

An important observation that is relevant to funding impact on higher education access is the trend in level of higher education attainment experienced in the United State in recent years. A Lumina Foundation report compared US attainment trends to international trends among developed countries. In this Lumina analysis attainment is described as “…high-quality postsecondary credential… leading to further education and employment.”7 An analysis of higher education attainment by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) found that the United States rank has fallen in the past decade to 11th among 15 economically advanced countries. Furthermore, US trends in attainment during the past decade have been flat while attainment levels in other developed countries have increased substantially.

In the context of these higher education attainment trends, the past and current state and federal policy directions related to higher education funding do not provide optimism for increased United States competitiveness internationally in higher education attainment and related economic development.

References

1 A Fifty State Look At Rising College Prices, Demos, February 2018

2 Tax Reform, Margaret Spellings, Chronicle of Higher Ed, November 30, 2017

3 Tax on Endowments Became Law, Chronicle of Higher Ed, March 8, 2018.

4 Final Tax Bill, Chronicle of Higher Ed, December 15, 2017

5 Passage of Senate Tax-Reform Bill, Chronicle of Higher Ed, December 1, 2017

6 Costs of Income Driven Repayment Plans and Loan Forgiveness Programs, US Dept. of Education Office of the Inspector General, January 31, 2018

7 Closing the Gaps in College Attainment, Lumina Foundation, April 2014

8 Higher Education State Policy Issues for 2018, AASCU, January 2018

Dr. Jay Noren M.D. 40-year career includes President of Wayne State University, Founding Provost of Khalifa University in Abu Dhabi, the founding Dean College of Public Health The University of Nebraska Medical Center, as well as the Executive Vice President and Provost for the University of Nebraska. is the Founding Director and Professor-Clinician Executive Master of Healthcare Administration Program, University of Illinois-Chicago College of Medicine and School of Public Health. He is a member of the Edu Alliance Advisory Council.

Edu Alliance is a higher education consultancy firm with offices in the United States and the United Arab Emirates. The founders and its advisory members have assisted higher education institutions on a variety of projects, and many have held senior positions in higher education in the United States and internationally.

Edu Alliance is a higher education consultancy firm with offices in the United States and the United Arab Emirates. The founders and its advisory members have assisted higher education institutions on a variety of projects, and many have held senior positions in higher education in the United States and internationally.

Our specific mission is to assist universities, colleges and educational institutions to develop capacity and enhance their effectiveness.